Latest News

Walking among the ‘Herd’

Michel Negreponte

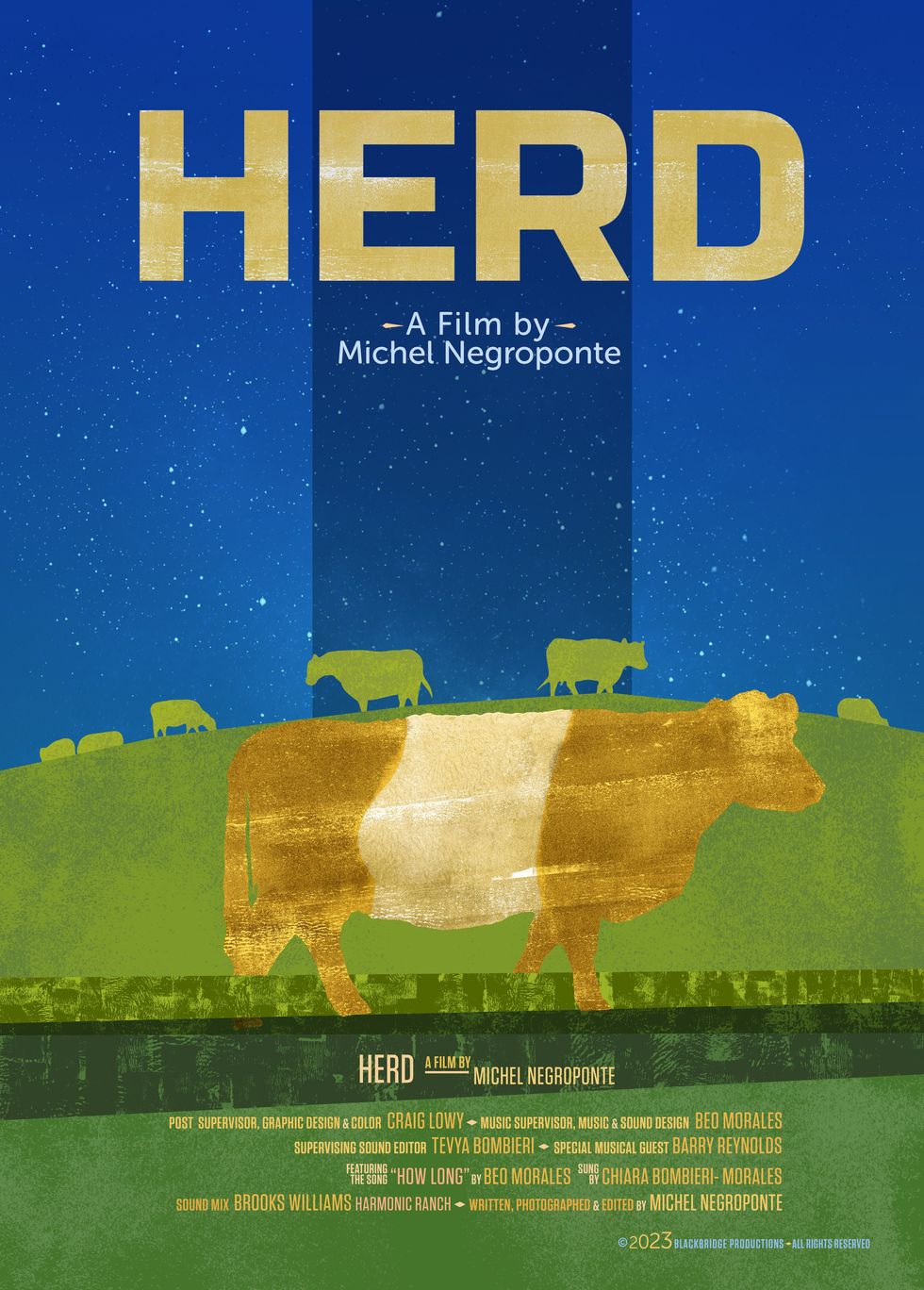

‘Herd,” a film by Michel Negreponte, will be screening at The Norfolk Library on Saturday April 13 at 5:30 p.m. This mesmerizing documentary investigates the relationship between humans and other sentient beings by following a herd of shaggy Belted Galloway cattle through a little more than a year of their lives.

Negreponte and his wife have had a second home just outside of Livingston Manor, in the southwest corner of the Catskills, for many years. Like many during the pandemic, they moved up north for what they thought would be a few weeks, and now seldom return to their city dwelling. Adjacent to their property is a privately owned farm and when a herd of Belted Galloways arrived, Negreponte realized the subject of his new film.

“You know, I’ve never made a nature documentary,” Negreponte shared. “That’s not really my thing, but once I found myself in upstate New York during the pandemic, I made several short films about the environment, about the land around me. They were mini essays, meditations. One of them was about my dog. That kind of led me into this longer project, which I also call an essay film. I’d like to say it’s a personal essay film, and a meditation.”

Early in the film, with the background of a heartbeat as soundtrack, a quote comes across the screen explaining, “Cows are adagio. 65 to 75 beats per minute.” This deliberate slowing down of pace lends a quiet to the narrative and allows for profound reflections on themes of motherhood, community, and humanity’s place in the natural world. “I think that the subject matter and the cows asked for a particularly delicate and peaceful approach. That is their temperament and their pace, and I certainly appreciate the vibe they give out,” Negreponte added.

Filmed throughout 2022, the film is chronological, following the herd through an erratic winter and the seasons of birth and death.

“It’s a very organic process,” said Negreponte of his technique of editing while filming. “It’s a process that I’ve developed over many years of making films and it suits the way I work.”

Using one camera, long shots linger on the lumbering giants as they navigate harsh weather, calve their young, protect, fight, and play with one another. Negreponte filmed parts of his own body in moments, “breaking the fourth wall,” as he explained, a technique that adds to the intimacy.

Throughout the film, there are other clips interspersed that Negreponte calls, “archival sections,” though not all the footage is historical. There are images of Hitler juxtaposed with images of Ghandi. The hunting and eventual extinction of wild Buffalo in the American West, and images showing reverence for cows in ancient cultures. From the horrors of industrial farming and animal exploitation to the clear communication and collective consciousness present, “Herd” confronts the viewer with humanity’s capacity for both cruelty and compassion.

By inviting audiences to slow down and reconnect with the natural world, “Herd” serves as a timely reminder of the interconnectedness of all living beings.

Negreponte shared, “I can’t help but think that people may think twice about their eating habits. I certainly think we can do better and adjust our diets so we’re less cruel to the animals around us.”

The owners of the farm have decided that the cattle are now pets, due in large part to the effect that “Herd” has had on them. The cows will now be used primarily to fertilize the fields.

Diego Ongaro

Parisian filmmaker Diego Ongaro, who has been living in Norfolk for the past 20 years, has composed a collection of films for viewing based on his unique taste.

The series, titled “Visions of Europe,” began over the winter at the Norfolk Library with a focus on under-the-radar contemporary films with unique voices, highlighting the creative richness and vitality of the European film landscape.

Ongaro has made two films himself. His second feature film “Down with the King” tells the story of a rapper who has come to recoup from career challenges on a farm in the Berkshires. Filmed on location in southwestern Massachusetts, it’s a beautiful movie with bucolic landscapes and moving performances by lead actor Freddie Gibbs.

The film premiered at the 2021 Cannes Film Festival (ACID section), won the top prize at the Deauville Film Festival, was released worldwide by Sony Pictures in 2022, and is currently available for viewing on Netflix. Prior to that, Ongaro’s first feature film "Bob and the Trees" had its world premiere at the 2015 Sundance Film Festival. Ongaro directed more than a hundred children’s programs for French Television in his early 20s and wrote and directed four acclaimed short films.

When asked how the idea for the series came about, Ongaro said, “Last year at the Norfolk Library I did a film series on the Berlin School, and the year before that it was on the French New Wave. I wanted to continue this cycle and offer a window on the cinema that I like.”

“Growing up in Paris, I’ve always had a diverse taste in cinema, watching American and French films, but also films from all over the world that allowed me to travel to places I’ll most likely never see. It was refreshing to see these stories anchored in different cultures. Now that I’ve been living away from native France for about 20 years, I gravitate mostly towards European cinema, probably seeking a culture and sensibility that I miss. A lot of these European films are incredible, offering complex characters and stories, unlike most of the American fare nowadays,” he adds.

The next and last installment happens Friday, April 12 from 7 to 8:30 p.m. and features “Swagger” by Olivier Babinet.

So how did Ongaro curate the films for this series?

“I like to share films that reflect my sensibility as a filmmaker and that most people haven’t seen. I’ve traveled to a lot of film festivals over the years where I got to see many films. I try to find themes within the films that have stuck with me. I like to think of it as a cine club. This year, the three films are all very different from each other, but each have a unique voice and form: a nuanced drama on the Baltic Sea titled ‘Afire’ by Christian Petzold, a hilarious nonsensical comedy called ‘Keep An Eye Out’ by Quentin Dupieux, and a gripping and wonderfully original documentary on teenagers going to school in a difficult projects in France called ‘Swagger’ by Olivier Babinet,” he said.

There were many films that didn’t make the cut due to time constraints, but Ongaro also recommends, “Reality” and “Yannick” by Quentin Dupieux as well as “Jericho,” “Barbara,” “Undine by Christian Petzold.”

As to what the audience can expect from the evening, Ongaro says, “It’s a casual affair. I give an introduction to the film with some backstory and context, talk about the filmmaker, the actors, and then we watch the film. We don’t do question and answer after, we don’t really have time for that, but people linger and talk about what they have just watched. People come to me with questions or to hear my take on an ending, a character. It’s fun to see how engaged people are after each screening.”

Screenings are free. Register on www.norfolklibrary.org.

Young native pachysandra from Lindera Nursery shows a variety of color and delicate flowers.

It is still too early to sow seeds outside, except for peas, both the edible and floral kind. I have transplanted a few shrubs and a dogwood tree that was root pruned in the fall. I have also moved a few hellebores that seeded in the near woods back into their garden beds near the house; they seem not to mind the few frosty mornings we have recently had. In years past I would have been cleaning up the plant beds but I now know better and will wait at least six weeks more. I have instead found the most perfect time-consuming activity for early spring: teasing out Vinca minor, also known as periwinkle and myrtle, from the ground in places it was never meant to be.

Planting the stuff in the first place is my biggest ever garden regret. It was recommended to me as a groundcover that would hold together a hillside, bare after a removal of invasive plants save for a dozen or so trees. And here we are, twelve years later; there is vinca everywhere. It blankets the hillside and has crept over the top into the woods. It has made its way left and right. I am convinced that vinca is the plastic of the plant world. The stuff won’t die. (The name Vinca comes from the Latin ‘vincire’ which means ‘to bind or fetter.’) Last year I pulled a bunch and left it strewn on the roof of the root cellar for 6 months and the leaves were still green.

Disposal is by bonfire, the least desirable method, but in this case the only way of ensuring it does not return.

2024 will be the year I begin to take it out, with sporadic help from hired hands. While they tackle larger areas of the offending plant, I have started from the fringes of the woodland interior and am working outward. Frankly it is not as boring from here as the vinca is less packed into the soil. It is an oddly satisfying task; this has to do with the vine-like nature of the plant. There is a knobby bit tethered to the soil by its roots; once this is lifted up (I use fingers but Norm, who is working in denser beds of the stuff, uses a hori knife) the vine runs to its next root knob about a foot or two away. It feels as if you have progressed quite a bit for one big tug. The same technique can be used on Glechoma, or ground ivy, although the vines are far thinner than those of vinca. I should be working on this well into the next decade.

While nurseries and garden centers continue to push vinca, there are native groundcovers that look great and can help to restore native habitats. Michele Palustra runs Lindera, a small outfit in Sharon that prioritizes local ecotypes of natives, meaning that she collects the seed herself from surrounding property, ensuring that the plants growing from them will serve local insects well. Spreading Jacob’s Ladder, Polemonium reptans, works in moderately shady circumstances, with its dense and deep green set of leaves and a truly beautiful pale purple or white flower. This plant comes to New England from south and west of the US but is hardy to zone 5. One of Michele’s favorites is native Allegheny pachysandra, Pachysandra procumbens.

Unlike the ever-present non-native Japanese pachysandra terminalis which is dying off thanks to Volutella blight, native pachysandra has a more delicate leaf and a showier flower. It is slower to spread than is the Japanese version but the use case is similar; as an underplanting around tree bases and to fill in around plantings in garden beds. I have recommended tiarella cordifolia as a pachysandra replacement for these purposes and suggest pairing either with a native fern such lady fern or maidenhair fern. Native ginger, asarum canadense, and the 200 or so native species of viola, or violet, work beautifully for groundcover; the former is excellent on hillsides where you can better see the shy burgundy colored flower, the latter spreads quickly which is a bonus and all sorts of insects feed on its flowers. Try to get the straight species of these native plants rather than a cultivar of them which may not benefit the habitat as well (this fascinating topic will be covered in the next installment of The Ungardener.)

I have purchased 50 plugs of Pennsylvania sedge, Carex pensylvanica, from the online consolidator Izel Native Plants to plant under cherry trees that have resisted any past attempts to have a downstairs neighbor. I also want to explore ways to encourage the growth of native moss which also makes an excellent groundcover.

Lindera, along with Tiny Meadow Farm, are having a pop-up spring sale in Sharon that I encourage you to visit. They will be selling truly gorgeous native plants including groundcovers.

This will take place Sunday, April 28 from 10-6 at Lindera Nursery, 60 Knibloe Hill Road in Sharon. www.tinymeadowfarm.com/events/spring-sharon-plant-sale.

Dee Salomon "ungardens" in Litchfield County.