The 55-acre Pope property on Salmon Kill Road is owned by the town of Salisbury and is being considered for affordable housing.

Photo by Debra A. Aleksinas

Editor’s note: This is the second of a series focusing on how land trusts are working in concert to tackle conservation challenges.

The vast forests and cold-water streams of rural Northwest Connecticut — centrally located in a multi-state habitat corridor known as the Berkshire Wildlife Linkage — are among the most climate-resilient and complex in Southern New England.

The region comprises the most intact forest ecosystem in Southern New England, with an estimated 75 percent forest cover, including 6,042 acres of contiguous forestlands in the towns of Norfolk and Falls Village owned and managed by the nonprofit Great Mountain Forest Corp.

“When we conserve land in this corridor,” said Catherine Rawson, executive director of the Northwest Connecticut Land Conservancy (NCLC), “we are bridging gaps” in wildlife and avian migration.

As a result, conservation and protection of these natural resources, which provide critical habitat for more than 320 rare species, falls heavily on the region’s land trusts and conservation groups, according to a new report, The Pace and Scale of Conservation in Northwest Connecticut, published by the Kent-based NCLC with input from 22 local land trusts.

Significant challenges

to meeting state’s goal

On the whole, Connecticut has a goal of protecting 21% of its lands and waters by 2023 with the state aiming to protect 10% and it is asking land trusts and other partners to protect 11%. However, Connecticut faces “significant challenges to meeting this goal since, based on its current pace of land acquisition, it will take at least 65 more years meet its 10% goal,” according to the NCLC report.

The research further reveals that Connecticut ranks at or near the bottom for conservation funding in New England, and its land values are among the most expensive in the country.

“Clearly these towns in the Northwest Corner have the most available conservation land compared to, for example, Fairfield County,” placing a greater burden on them, said Bart Jones, who retired in 2012 from a 40-year legal career in private practice in New York City and now serves as president of the Cornwall Conservation Trust (CCT), and is a board member of the Housatonic Valley Association (HVA), Great Mountain Forest and serves as an alternate on the Housatonic River Commission.

On the flip side, said Jones, development pressure has not yet become as severe an issue in Litchfield County as it has in some areas of the state, like Fairfield County, where a quarter of an acre of land can fetch as much as $750,000.

“The price of land up here really hasn’t gotten so expensive that a land trust in Litchfield County can’t save it. We’ve been lucky in that regard, but we shouldn’t become complacent,” Jones said.

33 partners comprise the Greenprint Collaborative

Connie Manes, director of the Litchfield Hills Greenprint Collaborative, touted the work being done by small land trusts in conjunction with the larger regional or state conservation groups.

“We participate in networks and initiatives outside of our immediate area but impacting our work, like the Berkshire Taconic and Hudson to Highands RCP’s (Regional Conservation Partnerships),” Manes explained.

The Greenprint is a network of aligned conservation organizations working together in Northwest Connecticut since 2008. There are currently 33 partners, according to Manes.

“The purpose of the Greenprint has always been to support each other and amplify each partner’s capacity, and to protect more land, with coordination, efficiency and the greatest environmental impacts,” Manes said.

Manes also noted that in addition to collaborating with each other, Northwest Connecticut’s land trusts work closely with their municipal leaders, serving on various town commissions like Inland Wetlands, Conservation Commissions and Planning and Zoning, and contributing open space and Follow the Forest connectivity priorities to municipal Plans of Conservation and Development (POCDs).

Community outreach and education is also a vital mission among conservationists, said Manes.

“We engage our local schools, churches, scout troops, volunteer organizations, senior centers and more in exploring and using the lands we’ve protected, and in learning about the management needs of the region through community science programs,”

In late October, numerous community partners joined the Washington, Conn.-based Steep Rock Association in co-presenting an episode of “Can This Planet (Still) Be Saved,” on the PBS public affairs program, Common Ground with Jane Whitney.

Whitney, a veteran journalist, and her husband, Lindsey Gruson, a former correspondent for the New York Times who is the show’s producer, have lived in the Litchfield County since 2005 and produce the program from their home.

Reconnecting, conserving region’s forests

The Follow the Forest regional initiative seeks to protect and connect forests and promote the safe passage of wildlife throughout the Northeast, from the Hudson Valley to the forests of Canada.

Sharon Land Trust, said its executive director Maria Grace, is a proud partner of this regional initiative, which aims to protect at least 50% of each core forest habitat that will anchor this key wildlife corridor, focusing on areas of greater than 250 acres.

This amount of forest patches is a scientifically recognized minimum need to sustain important woodland species such as bobcat, black bear, fisher and moose as they adapt to climate changes and find new habitats.

Sharon plays a needed role in this initiative because large patches of core forest still exist in our area, and they serve as refuges for wildlife, according to Grace.

“We still have a lot of land to protect,” she said.

Manes referred to a recent report from the Redding-based Highstead Foundation, “New England’s Climate Imperative: Our forests as a Natural Climate Solution,” which asserts that New England’s forests are “an underrated asset in the fight against climate change,” already sequestering the equivalent of 14 percent of carbon emissions across the six states.

“Through implementing five complementary strategies, we can expect forests to sequester 21 percent of carbon emissions while also enhancing critical co-benefits such as cleaner air and water, greater recreational opportunities, and jobs,” Manes noted.

Not all land created equal

Tim Abbott, director of HVA’s Greenprint Collaborative, explained that when it comes to conserving land, quality takes precedence over quantity.

“An isolated piece of land might not be a wildlife habitat or might not be connected to anything,” noted the long-time conservationist.

“It’s not just about accepting any old piece of land. We are being increasingly strategic rather than opportunistic. It means we are having important conversations. We have to be not only open to that but see it as part of our work,” said Abbott.

He said there are many considerations, or conservation values, that land trusts weigh before purchasing property, including whether it is farmland, wetlands, serves as a wildlife habitat, is part of a regional flyway initiative or can be linked to neighboring parcels.

“You can’t have a laundry basket of things you want on a property with equal weight,” he noted.

Conservation and the property tax quandary

In addition to its ecological and social benefits including recreational opportunities, land protection offers value to communities in the form of clean air and water, climate resiliency and preservation of cultural heritage

However, a common concern among individual taxpayers is that conserved land will increase their tax burden once that property is taken off the tax rolls.

“Every time we conserve land we are, in effect, taking a paycheck away from the town. That’s another pressure,” said Cornwall Conservation Trust’s Jones. That burden, he predicted, “is going to be a drag” on future conservation goals.

Jones further noted that that another issue on the property tax side involves state forest land, and the fact that the state has reduced payments to towns in lieu of taxes.

“The state should at least keep up with inflation,” he noted.

A January 2022 report by Harvard University, Amherst College and Highstead Foundation researchers, “Does Land Conservation Raise Property Taxes? Evidence From New England Cities and Towns,” found that “The changes in the rates attributed to new land protection were small.”

Specifically, a 1% increase in the percentage of town land protected was estimated to cause a 0.024% increase the tax rate, according to the report, which used data from more than 1,400 towns and cities in New England from 1990 to 2015.

Researchers noted, however, that tax-rate increases were somewhat higher when land protection occurred through municipal purchases or private easement protection, and that “more substantial” tax rate increases were found when towns were “growing slowly, had lower median incomes, fewer second homes and less land enrolled in current use programs.”

The size of these impacts ranged from $5 to at most $30 in additional taxes paid for each $100,000 in property value, according to the report.

Conservation and

affordable housing

Another pressure on conservation, said Jones, is the fear that conservation of land takes it away from development, including affordable housing.

“But the point is,” said the CCT president, “Cornwall, for example, is a huge town of 46 square miles, although many people don’t realize that” because its low population rate gives the impression that it is smaller.

“Even if we saved 38 percent, we would still have 18,000 acres left, which is larger than Darien, New Canaan and Hartford, yet people are saying we don’t have enough land for affordable housing.”

Jones said there is no reason conservation and affordable housing cannot peacefully co-exist. “It’s not an either/or” choice, he noted.

Thinking globally,

acting locally

A Kent farm is contributing to the town’s economy as well as to residents facing food insecurity.

In the last decade, 10% of Litchfield County’s population was designated as food insecure, and during the COVID-19 pandemic that percentage rose to 38.4 percent with as many as 25,000 Litchfield County residents experiencing food insecurity, according to the Kent Land Trust.

The number and frequency of visits to Kent’s food bank has doubled. In response, Kent Land Trust has partnered with Marble Valley Farm to offer fresh-picked produce each week to families using the Kent Food Bank.

“So many organizations are doing amazing things like this, said Manes. “What we are finding is that each hyper-local organization is able to be more nimble in responding to their community’s needs.”

The bottom line, she said, is that working together is the best, “and really the only, way,” for Northwest Corner land trusts to accomplish their visions and overcome the future challenges.

Land Conservation in Northwest Connecticut

— From 2010 to 2020, 9,772 acres in 253 transactions were protected by participating land trusts.

—The average transaction is 39 acres.

—During 2010 to 2020, land trusts averaged 23 transactions per year. However, in the last five years, the average number increased to 28 per year.

—A total of 1,406 acres were permanently protected by land trusts in Northwest Connecticut in 2020.

Source: Northwest Connecticut Land Conservancy

Author Anne Lamott

On Tuesday, April 9, The Bardavon 1869 Opera House in Poughkeepsie was the setting for a talk between Elizabeth Lesser and Anne Lamott, with the focus on Lamott’s newest book, “Somehow: Thoughts on Love.”

A best-selling novelist, Lamott shared her thoughts about the book, about life’s learning experiences, as well as laughs with the audience. Lesser, an author and co-founder of the Omega Institute in Rhinebeck, interviewed Lamott in a conversation-like setting that allowed watchers to feel as if they were chatting with her over a coffee table.

“I feel like I’m in my living room talking with my closest friends,” Lamott said.

In her 20th book, “Somehow: Thoughts on Love,” she goes back in time, writing about her own personal life experiences in a candid way, about her family, recovery and her faith. Lamott relates coming face to face with intense emotions and multiple epiphanies and lessons she’s learned.

The book explores the transformative power that love has in our lives: how it surprises us, forces us to confront uncomfortable truths, reminds us of our humanity, and guides us forward.

“Love just won’t be pinned down,” she says. “It is in our very atmosphere and lies at the heart of who we are."

“We are creatures of love,” she writes on her website describing the premise of the book.

Lamott is a progressive writer. She married for the first time at the age of 65, and has been sober for 37 years. She shares a life with her husband, Neal Allen, who is also a writer, her son Sam Lamott, and her grandson. Her family makes up the main characters throughout the book, reminiscing on escapades together.

“To have a heavy-hitting writer here is just wonderful, I have been following her since San Francisco, and when I heard she was in Poughkeepsie I bought tickets right away,” said Lamott fan Suzanne Sagan.

The Bardavon audience was filled with women from the ages of 34-70, some were able to convince their husbands to tag along and listen to the conversation. All attentive to her, laughing at the jokes and even attempting to sing her happy birthday.

Conversation topics ranged from the themes in her book, to sobriety, to telling stories about being a mother.

Learning about how to help yourself first, if you want to feel the love you have to spread the love, aging, relationships, having your cup filled full with your own water, and learning from your mistakes.

“That’s what life is like, slipping on a cosmic banana,” Lamott declared.

“As with all of her deceivingly simply rendered pieces, Lamott’s foibles are central to the 12 stories told here. Reconciling her own flaws as the key to tolerance is implied. Falling short is a given, especially when seeking to understand folks whose views are different from hers, particularly when they’re on the political spectrum. But demonstrating love to those who cause harm just might be too much of a reach for her — that stuff is for saints; it’s next-level wellness. Yet, Lamott strives,” Denise Sullivan writes for Datebook, a San Francisco Arts and Entertainment Guide.

Lamott was able to quote well known names such as Susan B. Anthony, Carrie Fisher, and Mother Theresa. During the conversation, she often turned to quotes that helped her create the mindset she has today, and spreads to the audience.

The talk was presented by Oblong Books in partnership with Bardavon Presents.

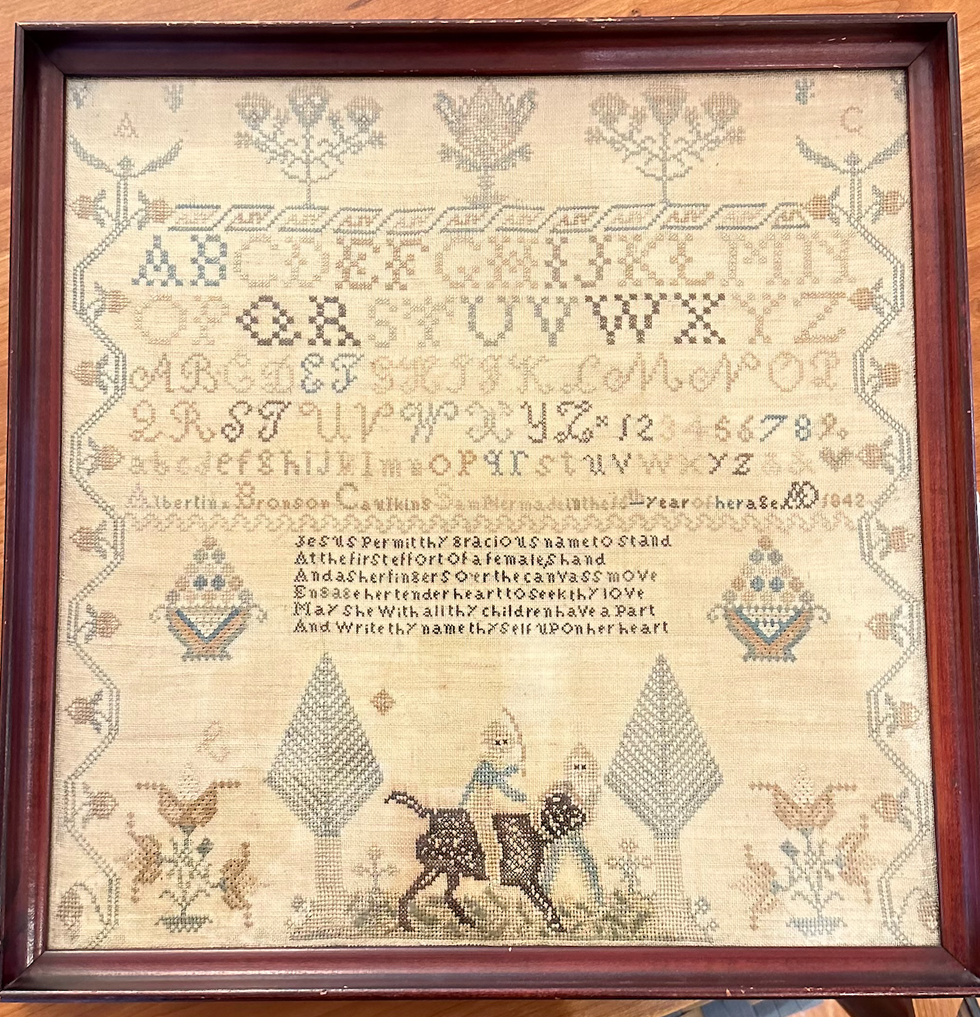

Alexandra Peter's collection of historic samplers includes items from the family of "The House of the Seven Gables" author Nathaniel Hawthorne.

The home in Sharon that Alexandra Peters and her husband, Fred, have owned for the past 20 years feels like a mini museum. As you walk through the downstairs rooms, you’ll see dozens of examples from her needlework sampler collection. Some are simple and crude, others are sophisticated and complex. Some are framed, some lie loose on the dining table.

Many of them have museum cards, explaining where those samplers came from and why they are important.

It’s not that Peters has delusions of grandeur, with those small black or white cards a part of the fantasy. In the past few years, her samplers have gone on outings to historical societies and exhibits. Those small black cards are souvenirs.

About 27 of the pieces from Peters’ collection have just left home again, and are featured at the Litchfield History Museum of the Litchfield Historical Society in an exhibit that Peters guest curated along with the historical society’s curator of collections, Alex Dubois.

The exhibit is called “With Their Busy Needles,” and it opens with a reception on Friday, April 26, from 6 to 8 p.m. (The exhibit will remain open until the end of November.) Peters will give a talk called “Know My Name: How Schoolgirls’ Samplers Created a Remarkable History” at the museum on Sunday, May 5, at 3 p.m.

Although Peters was first attracted to samplers as a form of art and craft, she has come to see them as something more profound. Each sampler tells a story, but you have to know how to read between the lines of thread and fabric. Peters has become an able and eloquent curator of what were once educational tools just for young girls and women. She can look at one and give an educated guess about who made it, how old they were, where they lived and how affluent their family was (or wasn’t).

Some samplers were made on linen, others were made with silk. Some linens are fine, others are rough and homespun.

“Some of my favorites are made on what’s called ‘linsey woolsey,’” Peters said. “It’s a mix of linen and wool that’s been dyed green. It was uncomfortable to wear, but it looks great on a sampler!”

Younger girls often worked first on learning darning stitches, and would make simple samplers with letters of the alphabet. More advanced stitchers might create genealogies or family trees. Peters particularly loves to find multiple examples from one family.

“I have a couple sets that were done by sisters,” she said, “and a collection from the family of Nathaniel Hawthorne,” the American author of “The Scarlet Letter.”

All samplers, though, show the importance of girls within families, Peters said.

“Parents were excited about their girls getting an education and coming out in the world and displaying their accomplishments. It’s different from what we think.”

“We tend to scorn or disrespect things made by women, particularly if they’re domestic. But before the Industrial Revolution, all work was done at the home, by women and by men. There weren’t jobs that you went to, you did the work at home. Samplers, and needlework, are the work of women, the work of girls.”

Samplers were rarely sold, Peters said, except ones made to help Southern Blacks to escape slavery.

“They were made anonymously and sold at anti-slavery fairs from the 1830s to the 1860s. I have one that can be used as a potholder and it says, ‘Any holder but a slaveholder.’ I have another that must have been a table runner that says, ‘We’s free!’ We’d see some of them as offensive now, but they weren’t at the time; they were joyful.”

Every sampler tells a story, and Peters is an able and entertaining interpreter of those tales. Learn more by visiting the Litchfield History Museum and seeing the exhibit (complete with explanatory museum cards) and come for her talk about samplers on May 5. Register for the opening reception and for the talk at www.litchfieldhistoricalsociety.org/exhibitions.