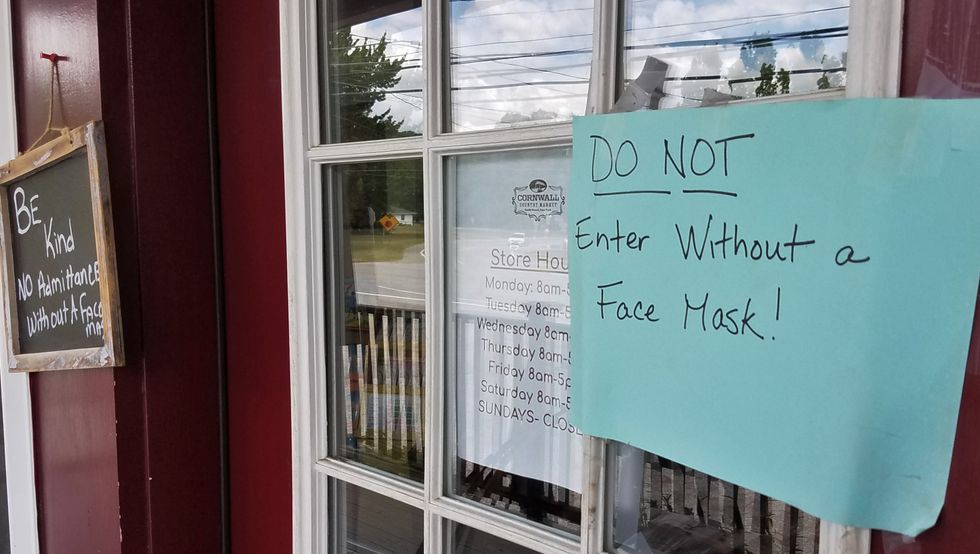

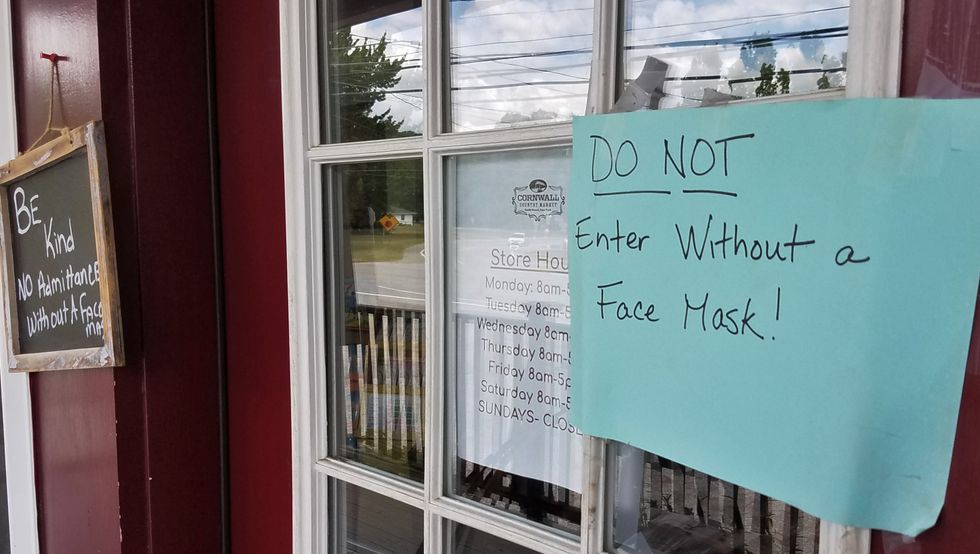

Two signs outside the Cornwall Country Market alert customers that they must wear masks inside the store.

Photo by Debra A. Aleksinas

A lone couple occupied a public bench along Kent’s Main Street on a recent Sunday morning as the town slowly came alive with people walking their dogs, dining outdoors or out for a drive.

Unlike most others around them who were sporting facial masks, this couple was bare-faced, and they intend to stay that way.

“It’s my choice, and I choose not to wear a mask. I don’t have to explain why to anybody,” said an adamant Justin Breecher, who was out enjoying a motorcycle ride with his companion through Litchfield County. “I keep my distance.”

As he spoke, a passerby who overheard the conversation paused and calmly uttered through his black face covering, “Not cool, dude,” and continued on his way.

The brief exchange, while hardly confrontational when compared to some explosive encounters nationwide between front-line workers and mask scofflaws, is indicative of the divisiveness that has erupted over mandatory mask requirements.

On April 20, in an effort to slow the spread of the coronavirus, Gov. Ned Lamont signed an executive order requiring everyone in Connecticut to cover their faces with masks or cloth coverings while out in public where social distancing cannot be maintained.

But the requirement is not a law, which means businesses like grocery and convenience stores, restaurants, bars and gyms are left to enforce those rules despite a lack of guidance from the state on how to do so. Across Connecticut and the nation, masks have become a flash point in the virus culture wars as people resume going out in public while coronavirus cases continue to surge.

Masks are like a vaccine

Recent health reports support wearing cloth facial coverings as a means of limiting transmission of the coronavirus.

Some people choose to wear masks for their safety and the safety of people around them. Others say they feel it is a violation of public liberty, or that the virus poses no danger or that masks are unattractive or uncomfortable.

“Masks are hot, ugly and make you feel stupid. The elastic loop always gets stuck over the arm of your glasses when you remove them to wipe off the condensation and you look even more stupid. Plus they’re un-American,” said Sharon epidemiologist Dr. James Shepherd, an infectious disease consultant at Yale-New Haven Hospital.

Masks, said Shepherd, who has worn them for decades, are no one’s favorite item.

“Nonetheless,” he said, “that fragment of material that covers your nose and mouth is like a cut-price vaccine.”

And here’s why: “A seasonal flu vaccine doesn’t protect you from flu 100%. In fact it is only about 50% effective in a good year.”

But 50% is still better than nothing, and, Shepherd said, “If you do get infected it also reduces the likelihood of you passing the flu virus on to someone else.”

A mask, he said, does exactly the same for the coronavirus.

“By wearing it you reduce the chances that infected viral droplets will be inhaled into your airway. In return, if you are infected your droplets will be trapped.”

Masks also seem to have a “significant effect” on reducing the efficiency of viral transmission, they allow us to “open up” safely again, and communities that have adhered to mask wearing among other things seem to be much safer than communities that haven’t, said Shepherd.

“It seems like a small price to pay.”

Jody Diaz, a customer at the Kent Mobil convenience store, echoed Shepherd’s sentiment.

“I don’t love wearing it,” she said referring to her fashionable bumble bee-themed mask. “Of course it’s uncomfortable. I look at it this way: Worst-case scenario is if I don’t wear it and somebody dies.

“That doesn’t seem like such a big sacrifice if I can keep people healthy,” said the Southbury, Conn., resident.

Pointing to a sign on the door of Kent Mobil advising customers to wear a mask, Diaz said she is also concerned about the burden resting on business owners to enforce mask policies that are a requirement rather than a law.

“It’s not something they signed up for when they opened their business. Many are also trying to deal with having just reopened after being shut down.”

‘I can’t enforce it’

Inside Kent Mobil, store manager Nee Maddumage said if a customer refuses to cover his or her face at his establishment, there is little he can do.

“I can’t judge. I don’t know if they have asthma or something. I can’t enforce it. The only thing I can say is ‘be supportive, wear a mask.’”

Maddumage estimated that about 98% of customers don masks, and that the scofflaws are few and far between.

“This community is so supportive,” he said, noting that several customers have donated large supplies of personal protective equipment (PPE) to store employees, including surgical masks and protective gloves, which he and his cashier were wearing.

At Stateline Pizza in North Canaan, owner Chris Christodoulou said when a customer comes into his restaurant bare-faced, he offers them a mask. Despite a notice on the front door announcing that masks are required, “If somebody doesn’t wear one, I can’t be the police, too, especially if it is a long-time customer. I have so many other things to worry about, and the rule is not law, so it’s difficult to enforce.”

But avoid confrontations

Bob LaBonne Jr., owner of LaBonne’s Market in Salisbury (with stores in Watertown, Prospect and Woodbury, Conn., as well), has enough on his hands trying to keep his employees and customers safe from COVID-19, so he has directed his employees not to confront mask-less customers for fear of triggering a confrontation.

“In the last three months we’ve banned more customers than in the last three years,” said LaBonne. Employees have been subject to “f-bombs,” rude behavior, refusal to wear masks or to have their temperature taken before entering the store, which is the store policy.

“I don’t engage with them. I want to be respectful.” But respectful only goes so far.

“We had one instance where we had to call the police,” said LaBonne, referring to a customer, a landscaper, in his 30s, who was shouting obscenities and refused to don a mask.

“He gave everybody a hard time” because he was not allowed to enter the store, said LaBonne. “I told him he was on private property and it was our choice if we chose to make [mask wearing] mandatory.” Not wanting to cause a disturbance, workers waited until the customer left and then summoned police. “They warned him not to come back,” said the store owner.

LaBonne, who sits on the reopening study committee for the Region One School District, is a staunch believer in the value of face masks in slowing the spread of the coronavirus.

On a recent committee conference call, he said, a physician pointed to a case in Missouri where two hairdressers who did not know they were COVID-19 positive potentially exposed 140 customers and six coworkers to the virus.

Face masks, said LaBonne, were credited with preventing transmission from that exposure.

The grocery chain owner has a message for anti-maskers: “One of my best friends spent 90 days at Yale,” fighting the coronavirus, said LaBonne. “For three crucial days, in the middle of it, he told me, ‘My only job was to breathe.’”

“In the end, when all of this is said and done,” added LaBonne, “we are all going to be judged by our actions.”

NORFOLK — Robert J. Pallone, 69, of Perkins St. passed away April 12, 2024, at St. Vincent Medical Center. He was a loving, eccentric CPA. He was kind and compassionate. If you ever needed anything, Bob would be right there. He touched many lives and even saved one.

Bob was born Feb. 5, 1955 in Torrington, the son of the late Joesph and Elizabeth Pallone.

Bob graduated from Babson College, one of the most prestigious accounting schools out there.

He built his own CPA practice in 1987. He was an accurate and accountable accountant. He would always say during tax season that taxes are an art not a science. He took time to teach his employees his art of taxes.

Bob was also a landlord and owner of the Royal Arcanum, where he met his long-time friend of over 20 years, Micheal Dinsmore. The two of them together experienced many great times. They would always be laughing and singing some of their favorite songs. Bob would always say that the Royal Arcanum was his baby. He loved that building and took great care of it. During his time at the Royal Arcanum and owning his business, he met a lucky lady, Melissa Baresi. Little did they both know that Robert and Melissa would become the best of friends and even turn into family. Melissa is considered to be Bob’s Girl. Bob is the reason Melissa has such a great life today.

After retirement, another one of Bob’s lifelong friends, Dana Devereux, was there to help Bob get accustomed to retirement. Retirement can be scary especially to a person who worked all his life. It was during this time that Bob was diagnosed with cancer again. Dana was there to lend a helping hand while Bob had to go through chemo.

Bob was truly a remarkable man and was blessed to have such great friends like Micheal, Melissa and Dana. He would always say if you can count the number of friends you have on one hand then you truly made it. Made it, Bob did.

A graveside service will be held on Wednesday April 17, 2024, at 2:00 p.m. at the Pond Town Cemetery in Norfolk, CT.

He will be buried next to his mom and dad where he always wanted to be.

Any memorial donations may be made to the ASPCA. Bob was an animal lover and had many cats throughout his life.

The Kenny Funeral Home has care of arrangements.

"Flowers" by the late artist and writer Joelle Sander.

The Cornwall Library unveiled its latest art exhibition, “Live It Up!,” showcasing the work of the late West Cornwall resident Joelle Sander on Saturday, April 13. The twenty works on canvas on display were curated in partnership with the library with the help of her son, Jason Sander, from the collection of paintings she left behind to him. Clearly enamored with nature in all its seasons, Sander, who split time between her home in New York City and her country house in Litchfield County, took inspiration from the distinctive white bark trunks of the area’s many birch trees, the swirling snow of Connecticut’s wintery woods, and even the scenic view of the Audubon in Sharon. The sole painting to depict fauna is a melancholy near-abstract outline of a cow, rootless in a miasma haze of plum and Persian blue paint. Her most prominently displayed painting, “Flowers,” effectively builds up layers of paint so that her flurry of petals takes on a three-dimensional texture in their rough application, reminiscent of another Cornwall artist, Don Bracken.

Sander’s first book, “The Family: The Evolution of Our Oldest Human Institution,” was published in 1978 while she worked as an instructor with the Institute of Children’s Literature. She described the history book, which took young readers on a journey of the evolving family unit from the Ice Age to the 1970s, as a kind of anthropological tour. “Kids are exposed to so many families in this culture,” she told The Lakeville Journal at the time. “I felt the book would give them a perspective on families in other cultures, both historical and contemporary. In 1992, The Lakeville Journal reviewed another of her published works, “Before Their Time: Four Generations of Teenage Mothers,” which Sander wrote as a faculty member at Sarah Lawrence in Westchester County, N.Y., where she served as the associate director of The Center for Continuing Education and taught modern American poetry. She was also a volunteer at a New York YMCA. At this YMCA, she met a young single mother named Leticia, whose trauma, struggles and hopes for the future inspired Sander to share Leticia’s story as told through the personal histories of the women who had come before her. Lakeville Journal writer Richard O’Connor called the book’s psychological exploration of cyclical poverty both “wonderful and disturbing.”

Her first slim volume of poetry, “Margins of Light” was available for attendees of the show to read while they examined Sanders’ paintings, a dual experience to take in the twin passions of her lengthy artistic career.

“Live It Up!” will be on view at The Cornwall Library through Saturday, May 18.

Rabbi Zach Fredman

On April 23, Race Brook Lodge in Sheffield will host “Feast of Mystics,” a Passover Seder that promises to provide ecstasy for the senses.

“’The Feast of Mystics’ was a title we used for events back when I was running The New Shul,” said Rabbi Zach Fredman of his time at the independent creative community in the West Village in New York City.

He has since relocated with his family to Germantown and founded Temenos, “a home for ritual and creativity that honors the wild humanity of all people,” as the website explains (temenosnyc.com). At these feasts, Fredman and his brother, a chef, would create a menu to highlight the symbolism and mythology of certain Jewish holidays.

“People loved it,” explained Fredman. “It’s kind of a two-pronged approach, a way to engage and digest symbolism through the belly.” The Seder (which means “order” in Hebrew) at Race Brook will be such an immersive experience: a four-course meal conducted in four parts, echoing the four cups of wine consumed during the ceremony.

Alex Harvey, arts programmer at Race Brook, and his wife, Sophia Akilova, have known Rabbi Fredman through various communities and music circles for many years. After moving to the Hudson Valley from Brooklyn, Akilova was “looking everywhere for some kind of Jewish community that was dynamic. There’s plenty of progressive Jewish communities,” Harvey continued, “but she was looking for something way more particular, a community that is rediscovering active prayer, actually somatic spirituality.”

Fredman spoke of Passover as an opportunity to reconnect with tradition while investigating present day reality through the core liberatory framework of the holiday. He said, “One of the major successes in Judaism is that the tradition was conceived as living. There’s the written material that’s passed on, that’s unchanging, but it’s always accompanied by oral teachings, teacher to student, teacher to student. And so there is a sense that tradition is alive and dependent on people making it fresh, making it new.”

The tradition will be made new once again with the addition of music at Race Brook by the powerful and virtuosic Duo Andalus with vocalist Lala Tamar. Tamar and Fredman, who is an incredibly accomplished musician as well, have been collaborating through Fredman’s group Epichorus for many years. Fredman will join Duo Andalus throughout the evening and the following evening (April 24), Epichorus featuring Tamar and Yacouba Sissoko, who plays the African Kora, will perform.

There are four questions that are asked during a Passover Seder, traditionally by the youngest person at the table. One of those questions is: “Why is this night different from all other nights?” Much of the rest of the Seder is in response to this question. When asked this particular question, Rabbi Fredman offered, “It’s been so overwhelming to watch the news cycle. It’s been a year where Judaism, Jewish identity, Jewish ethics, all of these things are completely different from what we thought they were even a year ago.” Fredman went on to speak about the fracturing that is occurring within the Jewish community and offered, “One of the functions of ritual, especially a ritual like this one, is to create space for people to have the conversations that we need to have.”

Creating a safe container for difference and for questioning is a tall order and one that Fredman meets with humility and curiosity. Of the Passover Seder he shared, “I’m hoping that in addition to the elements of food, and music, and teachings that there’s also space for people to be vulnerable and sift through some other profound experiences, painful experiences of the last six months and then, you know, investigate, turn things over and find something about themselves that helps us make sense of a disorienting moment.”

Reservations for Feast of Mystics, and The Epichorus featuring Yacouba Sissoko and Lala Tamar can be made at rblodge.com.