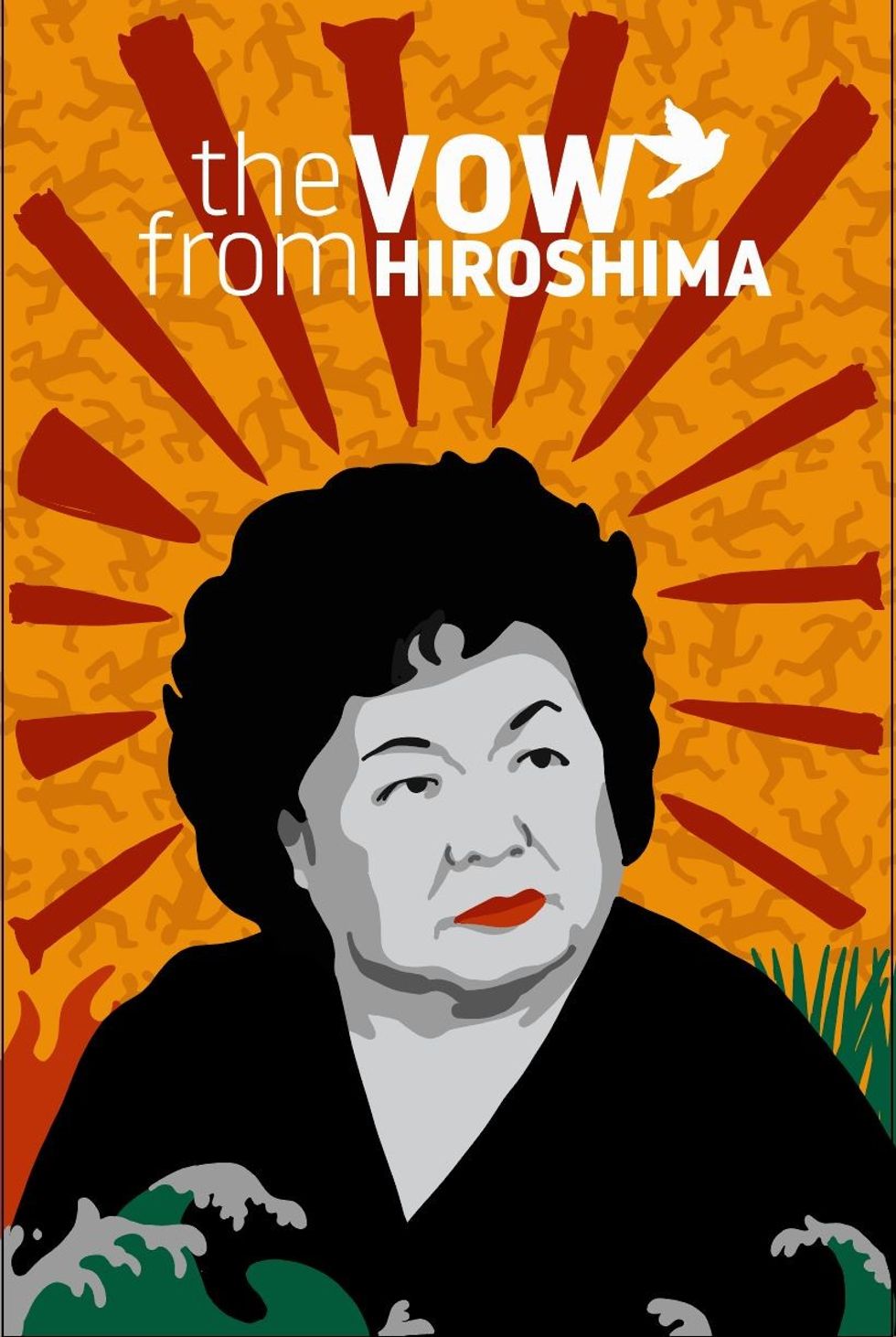

Courtesy of Bullfrog Films

On August 6, 1945, America dropped an atomic bomb on the Japanese city of Hiroshima killing over 70,000 citizens from both the blast exposure and the effects of radiation. A survivor of the bombing, 91-year-old Setsuko Thurlow has made nuclear disarmament her life’s mission, earning her The Nobel Peace Prize in 2017. Her story is documented in the film “The Vow from Hiroshima,” produced and written by Mitchie Takeuchi and directed by Sharon, Conn., resident Susan Strickler. I spoke with Takeuchi and Strickler in anticipation of a screening of the documentary for The Salisbury Forum.

Alexander Wilburn: Can you tell me about your first time meeting Setsuko Thurlow and how "The Vow from Hiroshima" came about?

Mitchie Takeuchi: The first time I met her was through the a program called Hibakusha Stories, hibakusha meaning the survivors of the atomic bomb. I met Setsuko through this educational program where she was going to speak at New York City high schools to share the hibakusha experience as a survivor firsthand. I was there as an interpreter — Setsuko didn’t need an interpreter, but there were other survivors from Japan so I was helping them.

Susan Strickler: Mitchie got me involved with Hibakusha Stories. As a group we went to a program at the Truman Little White House, and that was the first time where I really spent more time with Setsuko. At first I think she found me to be too opinionated, so we didn’t initially have the most warm and fuzzy relationship, but eventually we did. We did a trip to Vienna, which is portrayed in the film, where she was the keynote speaker at two major conferences. Her husband had recently died and she was trying to find a new balance in her life. Her husband had helped her write her speeches. She was saying “I don’t know how much longer I can do this, and I don’t really see myself writing a book.” I told her, she’s so charismatic, and she is both fierce and a delightful person to spend time with, someone should make a documentary about her. But I was a soap opera director, I certainly wasn’t thinking of myself. Then the next year in 2015 she was nominated for the Nobel Prize and was also going to be a part of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Conference which meets every five years, plus it was the 70th anniversary of the dropping of the bomb — it seemed like there was a lot happening and someone had to capture it. So without a script or money, I enlisted someone I knew through New York Women in Public Television who was a camera person. Over time, Setsuko and I became very close. I had quibbled in the beginning with the way she talked about certain things. She gave a speech at the Truman White House and we had an argument about that.

AW: What was the conflict?

SS: During her speech she referred to the dropping of the bomb as a war crime and compared it to the concentration camps. And some people got up and left because they were offended. Americans are still very sensitive about owning the fact that they were the first to drop the bomb. It may be what she thinks, but I didn’t think it was judicious of her to say that.

AW: In the film she talks about not wanting to be a figure of tragedy and sympathy, but focus on pushing policy forward. How did you balance that while also conveying the horror of her past?

MT: When we started to make the film we were purely focused on following her life because it was more like an autobiographical piece. It was a substitute for her wanting to write a book. We weren’t necessarily trying to capture the nuclear ban movement, but as it started moving forward very rapidly with the Nobel Prize, it became part of the narrative.

SS: When we started we were purely looking at Setsuko’s story to understand the humanitarian impact of nuclear weapons, but we were frequently shocked while filming how little Americans knew about the bombing — we had an adult say, “I didn’t know there were survivors.” People didn’t know that the U.S. occupied Japan for several years.

AW: What' the reaction been from the younger generations as you’ve shown the film? For students there seem to be a barrage of threats, from gun violence in schools to climate change, have you found it impacts the way they view the topic?

MT: We’ve shown the documentary to university and high school classes and the reception has been so encouraging. Gen Z are so surrounded by environmental issues and violence, they’re much more open to listening to our stories because I think they can relate to it.

AW: That’s what I was thinking while watching the film.

MT: It is a very realistic scenario for them, especially because of the environmental impact of nuclear weapons and climate chaos. I think young people are able to see through a lot of political elements for the sake of saving the planet. It’s very encouraging.

SS: This film started with the program called Hibakusha Stories, and the survivors couldn’t really go on because they’re in their late 80s and 90s, and Setsuko, who is still very engaged in the movement, has started to use the film as a way to tell her story. It really saves her emotionally, and frees her to focus on policy, which is what she’s really interested in now.

AW: In the film we see Setsuko being awarded the Nobel Prize with ICAN (The International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons) director Beatrice Fihn. Fihn told Time this week that she feels the possibilities of banning nuclear weapons have backslid. Since the invasion of Ukraine, do you feel the conversation around the film has changed?

MT: I think audiences are way more engaged in this subject now. Ever since Donald Trump and North Korea, there's been a shift in awareness, but particularly with the invasion of Ukraine and Putin using nuclear weapons as a threat, people in the United States are so much more interested. It’s unfortunate, but we really do need to utilize this awareness.

SS: When we started making this film, and we were going to foundations trying to get grants, we were frequently met with “Nuclear weapons? That’s so 1980s!” It was very discouraging and we always felt like we were pushing a rock up a hill. Now there’s so much more interest, and even though Beatrice may be saying it’s harder to advance policy towards disarmament, I think more people realize there’s a need. The general population, who were kind of asleep until Trump and then the invasion of Ukraine, they’re awake.

Screening and Q&A on Jan. 15 at The Moviehouse in Millerton, N.Y.

Author Anne Lamott

On Tuesday, April 9, The Bardavon 1869 Opera House in Poughkeepsie was the setting for a talk between Elizabeth Lesser and Anne Lamott, with the focus on Lamott’s newest book, “Somehow: Thoughts on Love.”

A best-selling novelist, Lamott shared her thoughts about the book, about life’s learning experiences, as well as laughs with the audience. Lesser, an author and co-founder of the Omega Institute in Rhinebeck, interviewed Lamott in a conversation-like setting that allowed watchers to feel as if they were chatting with her over a coffee table.

“I feel like I’m in my living room talking with my closest friends,” Lamott said.

In her 20th book, “Somehow: Thoughts on Love,” she goes back in time, writing about her own personal life experiences in a candid way, about her family, recovery and her faith. Lamott relates coming face to face with intense emotions and multiple epiphanies and lessons she’s learned.

The book explores the transformative power that love has in our lives: how it surprises us, forces us to confront uncomfortable truths, reminds us of our humanity, and guides us forward.

“Love just won’t be pinned down,” she says. “It is in our very atmosphere and lies at the heart of who we are."

“We are creatures of love,” she writes on her website describing the premise of the book.

Lamott is a progressive writer. She married for the first time at the age of 65, and has been sober for 37 years. She shares a life with her husband, Neal Allen, who is also a writer, her son Sam Lamott, and her grandson. Her family makes up the main characters throughout the book, reminiscing on escapades together.

“To have a heavy-hitting writer here is just wonderful, I have been following her since San Francisco, and when I heard she was in Poughkeepsie I bought tickets right away,” said Lamott fan Suzanne Sagan.

The Bardavon audience was filled with women from the ages of 34-70, some were able to convince their husbands to tag along and listen to the conversation. All attentive to her, laughing at the jokes and even attempting to sing her happy birthday.

Conversation topics ranged from the themes in her book, to sobriety, to telling stories about being a mother.

Learning about how to help yourself first, if you want to feel the love you have to spread the love, aging, relationships, having your cup filled full with your own water, and learning from your mistakes.

“That’s what life is like, slipping on a cosmic banana,” Lamott declared.

“As with all of her deceivingly simply rendered pieces, Lamott’s foibles are central to the 12 stories told here. Reconciling her own flaws as the key to tolerance is implied. Falling short is a given, especially when seeking to understand folks whose views are different from hers, particularly when they’re on the political spectrum. But demonstrating love to those who cause harm just might be too much of a reach for her — that stuff is for saints; it’s next-level wellness. Yet, Lamott strives,” Denise Sullivan writes for Datebook, a San Francisco Arts and Entertainment Guide.

Lamott was able to quote well known names such as Susan B. Anthony, Carrie Fisher, and Mother Theresa. During the conversation, she often turned to quotes that helped her create the mindset she has today, and spreads to the audience.

The talk was presented by Oblong Books in partnership with Bardavon Presents.

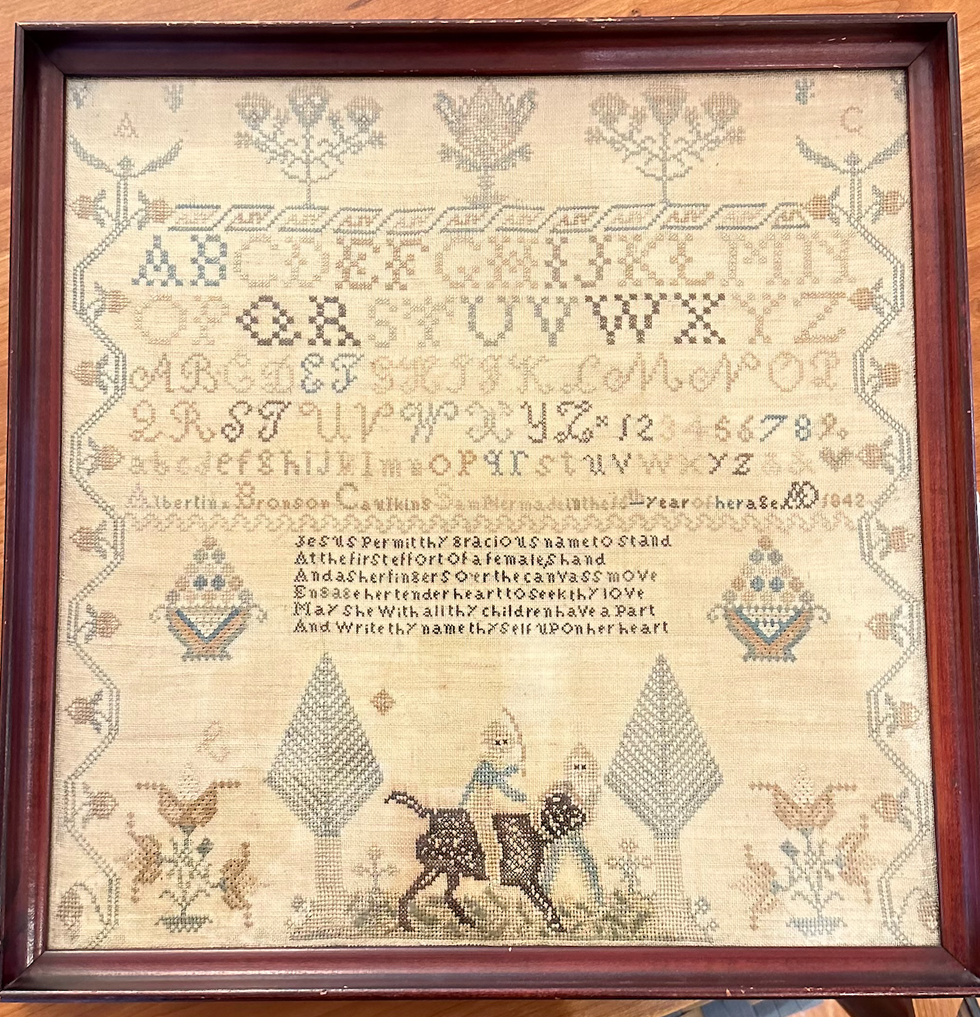

Alexandra Peter's collection of historic samplers includes items from the family of "The House of the Seven Gables" author Nathaniel Hawthorne.

The home in Sharon that Alexandra Peters and her husband, Fred, have owned for the past 20 years feels like a mini museum. As you walk through the downstairs rooms, you’ll see dozens of examples from her needlework sampler collection. Some are simple and crude, others are sophisticated and complex. Some are framed, some lie loose on the dining table.

Many of them have museum cards, explaining where those samplers came from and why they are important.

It’s not that Peters has delusions of grandeur, with those small black or white cards a part of the fantasy. In the past few years, her samplers have gone on outings to historical societies and exhibits. Those small black cards are souvenirs.

About 27 of the pieces from Peters’ collection have just left home again, and are featured at the Litchfield History Museum of the Litchfield Historical Society in an exhibit that Peters guest curated along with the historical society’s curator of collections, Alex Dubois.

The exhibit is called “With Their Busy Needles,” and it opens with a reception on Friday, April 26, from 6 to 8 p.m. (The exhibit will remain open until the end of November.) Peters will give a talk called “Know My Name: How Schoolgirls’ Samplers Created a Remarkable History” at the museum on Sunday, May 5, at 3 p.m.

Although Peters was first attracted to samplers as a form of art and craft, she has come to see them as something more profound. Each sampler tells a story, but you have to know how to read between the lines of thread and fabric. Peters has become an able and eloquent curator of what were once educational tools just for young girls and women. She can look at one and give an educated guess about who made it, how old they were, where they lived and how affluent their family was (or wasn’t).

Some samplers were made on linen, others were made with silk. Some linens are fine, others are rough and homespun.

“Some of my favorites are made on what’s called ‘linsey woolsey,’” Peters said. “It’s a mix of linen and wool that’s been dyed green. It was uncomfortable to wear, but it looks great on a sampler!”

Younger girls often worked first on learning darning stitches, and would make simple samplers with letters of the alphabet. More advanced stitchers might create genealogies or family trees. Peters particularly loves to find multiple examples from one family.

“I have a couple sets that were done by sisters,” she said, “and a collection from the family of Nathaniel Hawthorne,” the American author of “The Scarlet Letter.”

All samplers, though, show the importance of girls within families, Peters said.

“Parents were excited about their girls getting an education and coming out in the world and displaying their accomplishments. It’s different from what we think.”

“We tend to scorn or disrespect things made by women, particularly if they’re domestic. But before the Industrial Revolution, all work was done at the home, by women and by men. There weren’t jobs that you went to, you did the work at home. Samplers, and needlework, are the work of women, the work of girls.”

Samplers were rarely sold, Peters said, except ones made to help Southern Blacks to escape slavery.

“They were made anonymously and sold at anti-slavery fairs from the 1830s to the 1860s. I have one that can be used as a potholder and it says, ‘Any holder but a slaveholder.’ I have another that must have been a table runner that says, ‘We’s free!’ We’d see some of them as offensive now, but they weren’t at the time; they were joyful.”

Every sampler tells a story, and Peters is an able and entertaining interpreter of those tales. Learn more by visiting the Litchfield History Museum and seeing the exhibit (complete with explanatory museum cards) and come for her talk about samplers on May 5. Register for the opening reception and for the talk at www.litchfieldhistoricalsociety.org/exhibitions.